2019 Annual Report

To My Investors,

We had a good year in 2019. Most of you had gains in your equity portfolios of around ___%, which was ___ of the 31.5% gain for the stock market. Our portfolio businesses had a good year, in aggregate, but our stocks outperformed those business results significantly.

This year, I made some subtle changes to our investment strategy to target higher quality companies. In this letter, I will explain the reasoning for those changes and how those changes have reduced the business risk we’re taking across the portfolio. After examining those changes, I will discuss the performance of this year’s portfolio companies, examine how high current valuations will most likely lead to lower investment returns over time, and address the significant concentration of our portfolios. Finally, we will look ahead to the future and examine how we’re positioned to deal with a more challenging environment.

Our New(ish) Strategy

Dialing In Hurdle Rates

In previous letters, I described my strategy as follows:

My strategy is to act like a private market investor – find an excellent business run by able and honest management and wait to invest until I see the potential for at least a 4x return over 10 years.

I would keep most of that description the same, but after reviewing my mistakes over the past few years, I have seen that the majority of my bad decisions were made because I was taking too much risk trying to make that 4x, 10 year return. As a result, I’m taking my hurdle rate down.

Instead of using one blanket hurdle rate, what makes the most sense to me is to build hurdle rates on top of opportunity costs. I’ll discuss opportunity costs as I see them in the public equity markets today, understanding that in different scenarios, the numbers could be different.

This isn’t exactly textbook investing 101, but I personally build my opportunity cost numbers off of Berkshire Hathaway. Berkshire Hathaway is diversified, financed conservatively, and rationally managed (full writeups here and here for more detail). The stock also tends to trade frequently at a level where a long-term investor could expect 8-10% after-tax annual returns.

Every other public company I’m aware of carries more risk than Berkshire, mostly just because of specific business risk. Given higher risk, if I’m going to own anything else, I need to see a clear path to make more than 8-10%.

The way I’ve decided to move out the risk curve is to increase my hurdle rate to compensate for higher financial risk. Berkshire has significant net cash and can make us an after-tax IRR of 8-10%. If a potential investment is unlevered, then I’m okay investing in it if I think I can make 10% IRRs. For any investment grade borrower, my hurdle rate will be 12% IRRs, and for a high-yield borrower I want 15%+ IRRs.

On a blended basis, this has taken the hurdle rate down from the old rate of 15% IRRs. Given that none of us actually needs to make 15%, this will let us take less risk to try to make a return that is adequate to meet our long-term financial goals.

Choosing Quality

The second change this year is that I have consciously moved us into higher quality investments. “Quality” is a difficult word to define but is a bit simpler to broadly describe. When I think of a quality business, I think of one that is very likely to succeed over time in almost any environment.

With my prior goal to make us 15% IRRs, sometimes I knowingly sacrificed business quality in order to buy a cheap, often highly leveraged company where we’d make a killing if things worked out like I hoped but where we would lose significant money if the business didn’t perform well. Since the quality was generally low, these businesses mostly didn’t grow like I hoped they would and results were subpar. In striving to make a high return, I was buying things I shouldn’t, taking too much risk, and hurting performance.

Obviously, buying higher quality companies is no panacea. Many investors make great returns buying cheap, lower quality companies, and many investors make poor returns by overpaying for higher quality companies. Each of us has certain strengths and weaknesses, and frankly I’m just not very good at investing in lower quality companies. We’ve made almost all our money investing in great companies at reasonable prices, and I’ve made the majority of my mistakes in lower quality companies at cheaper prices. Going forward, I’m going to try to do more of what I’ve historically been good at.

After selling off our investments in these lower quality companies this year, we now own a more concentrated group of better companies. With a slightly lower hurdle rate, we can own more great businesses that trade somewhere around what they’re worth; I don’t need to be putting us into higher risk situations in order to hopefully make 15%.

Activity In 2019

Although the strategy might be slightly different than it was one year ago, and although I reduced the amount of stocks we own from 14 to 8, our portfolios are fairly similar to last year.

I sold our smaller investments - Tencent, Facebook, Bank OZK, Liberty Global, Liberty Latin America, Nexstar, and Post Holdings - and mostly redeployed the money into the higher quality things we already owned - Transdigm, energy pipelines, Constellation Software, Charter, Brookfield Asset Management, and Berkshire Hathaway. We owned all of those stocks last year, it’s just that now we own more of them.

Separate from these movements in the smaller positions, I also made two larger changes in the portfolio. First, in our pipeline investments, I sold our position in Kinder Morgan and used the proceeds to buy more Magellan Midstream Partners and eventually to start a position in Enterprise Products Partners. Second, I bought a significant stake in Wells Fargo. I will detail those changes in the next section.

Business Performance

In this section, we will examine how our investments have done this year. I will focus on business results and my estimates of intrinsic value growth. For this section, I like to use a constant free cash flow or EBITDA multiple to loosely track intrinsic value growth over time. The goal isn’t to use the “right” multiple, but just to use one around where the company usually trades, so I can look at value creation.

Since there were some wild valuation swings this year, I will discuss valuations and what those mean for our portfolio in the subsequent section.

Transdigm

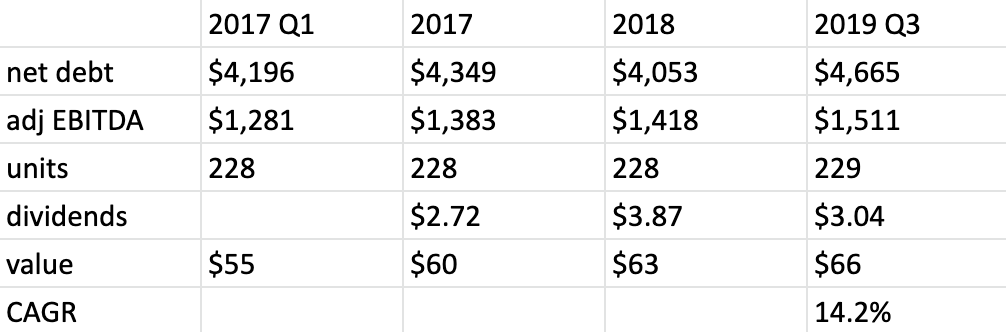

Transdigm, our largest position, was our best performer in 2019. Here are pro-forma financials starting from when we initially bought shares until today:

The equity value is up roughly 50% since the end of 2018 after factoring in a $30 dividend. Transdigm was primarily able to create so much value because of its acquisition of Esterline.

Transdigm acquired Esterline in March, and at that time, the company had ~15% EBITDA margins. In the quarter spanning July - September, so roughly 4-7 months after the initial purchase, Transdigm has already increased EBITDA margins up to roughly 30%.

Nine months after the acquisition, Transdigm has invested a net of $2.9bb and is generating run-rate EBITDA of almost $500mm. Given Transdigm’s net debt / EBITDA ratio of ~6x, the company has effectively recapped all of its equity out of the transaction. If Esterline’s EBITDA is worth 15x, Transdigm has created roughly $4.5bb in value for its shareholders already, with room for more value creation going forward if they can further increase margins closer to legacy Transdigm levels around 50%.

We have now owned Transdigm for 6 years. Over that time, the intrinsic equity value is up ~290%, or at a rate of 25.5% annually, after adding in the significant dividends we have received to the above chart. Going forward, acquisitions will almost certainly add less value than they have historically as the company gets bigger and its opportunity set stays roughly the same. Even so, given its attractive end markets and returns on capital, I still see strong returns going forward even without acquisitions.

Energy Pipelines - Magellan Midstream Partners and Enterprise Products Partners

I made two large changes to our energy pipeline holdings this year. First, I sold our position in Kinder Morgan to buy more shares in Magellan Midstream Partners. Second, later in the year, I sold about half of our Magellan stock to buy shares in Enterprise Products Partners. At this point, we have about 15% of our money in energy pipelines, with half of that money invested in Enterprise and half in Magellan.

The decision to sell Kinder Morgan was a relatively easy one. We initially bought shares because they were very cheap. Over a year or so, the valuation caught up to roughly equal the valuations of its peers, which have better assets and are more conservatively financed, so we sold Kinder Morgan and used the proceeds to buy shares of its obviously better competitors. First, I bought additional shares of Magellan, then later in the year, I bought some Enterprise as well.

Since we have only owned Enterprise for one quarter, I’ll skip the discussion of the business results. On the other hand, we have now owned Magellan for almost three years, and the company has performed quite well over that time. Here’s a chart showing value growth at a constant run-rate 13x EBITDA multiple for the company:

Intrinsic value is up at a ~14% annual rate. The company has invested in new projects for growth, paid out excess cash flow to investors, and sold assets when it has made sense, all while keeping a very conservative financial profile.

While the business has done well, our investment has not. We have only made about ___% annually on our initial purchases while the business has increased its value by the aforementioned ~14% rate. The error here is mine. I initially overpaid for our position, expecting a level of growth that now appears like it will not occur. We needed somewhere around $750mm of annual growth capital expenditures over time to make the returns I wanted from our initial purchase price. Actual growth capex over the next 5 years or so looks like it will fall well below that $750mm annual number.

As a consequence of reduced growth expectations, Magellan’s premium valuation compared to its peers has justifiably come down. Even so, I am continuing to hold shares for us. I still believe Magellan can make an attractive return over time from this reduced valuation and even with much lower growth capex estimates, I still see the possibility for 12%+ returns.

Enterprise has a similar story to Magellan but with a couple of important differences. It finances itself conservatively and has historically allocated capital well, although not quite as well as Magellan. To make up for this, it has a more diversified and higher quality asset network and trades a bit cheaper in relation to its cash flow. I also see 12%+ returns with conservative assumptions for Enterprise.

Constellation Software

We have owned Constellation Software for almost three years. Over that time, earnings are up ~57%, or at a rate of ~18% annually. The company continues to execute its business plan, running its numerous businesses efficiently and using their cash flow to buy more software companies at impressive rates of return.

The biggest challenge for the company in the future will be to continue to spend large amounts of money on small, accretive acquisitions. I have been pleased at the rate of growth of Constellation’s spending over the last few years, and if they can keep the acquisition pace flat over time or grow it, then the company should be able to continue to drive mid-teens annual earnings growth.

Charter Communications

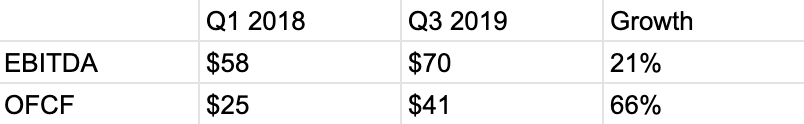

We have owned Charter for about 1.5 years. Calculating intrinsic value growth is a bit more complicated in this case due to significantly falling capital intensity. Here is EBITDA and OFCF (defined as EBITDA - capex) per share over the time we have owned the company, along with the total growth rates:

Investors ultimately care about OFCF, but it would be disingenuous to say that the value of Charter’s equity is up 66% over the past 1.5 years. Investors had been expecting a fall in capital intensity and were paying up for that somewhat when we initially bought shares - we effectively paid a high multiple on trailing OFCF but a much lower multiple on expected OFCF a couple of years out.

So I think it’s fair to say that intrinsic value growth has been somewhat higher than 21% but definitely not 66%. Obviously that’s a wide range, but it’s clear the business has performed quite well.

Going forward, I expect some continued improvement in capital intensity along with modest EBITDA growth. Given the company’s leverage and capital allocation strategy of using all cash flow and incremental debt for buybacks, that could still generate strong intrinsic value growth over time.

Brookfield Asset Management

We have owned Brookfield for almost two years. The company, due to its complexity, needs to be valued on a sum of the parts (SOTP) basis. If we use the market prices of its significant investments in public securities, then the intrinsic value is up at an annualized rate of ~15% over that time.

Some of this gain is a result of investors bidding up the public securities to valuations that are much higher than I would be comfortable paying. After adjusting Brookfield’s SOTP to reflect my lower valuations, the intrinsic value is up in the range of 10-12% annually.

Brookfield’s growth in value has been mostly driven by increased AUM in its private funds business as institutional investors look to real assets to generate returns. This is a very good business that should continue to grow over time.

On the other hand, about 40% of Brookfield’s value lies in 4 separate publicly traded entities that Brookfield manages and also in which it is a large investor. I do not like how Brookfield manages these entities - they have lots of leverage, pay out too much of their cash flow in dividends, and have misaligned incentives up to the parent - and Brookfield has done a few things this year that have made me even more uncomfortable with these companies. I worry longer term that mismanagement will have negative repercussions for its very valuable asset management operation.

For now, I am simply valuing these businesses well below their public market values, and keeping our shares still makes sense even with these lower values. Longer term, I will be watching these businesses for any signs that they’re impacting Brookfield’s ability to grow its asset management business.

Berkshire Hathaway

Berkshire continues to perform well for us. Since we initially bought shares six years ago, the intrinsic value of the company has compounded at about 11.5% per year, and the stock has made a ____ return. That number has been boosted by stock market returns much higher than long-term averages along with the tax cuts last year.

I expect future annual gains in intrinsic value somewhere in the range of 8-10% (refer to the write-ups linked above for a detailed discussion). Berkshire will never be the investment we own with the most potential for gain, but it has as little risk as you could ever hope for in a stock. We will likely continue to allocate some money into Berkshire, especially if I’m struggling to find other good ideas.

Wells Fargo

Wells Fargo is a new addition this year. For a full write-up of my reasons for owning this stock, see this link. In short, Wells has been horribly mismanaged over the past few years, but the company has largely kept its customer base. Poor management has mostly manifested itself in Wells Fargo’s cost structure, which is roughly 1500 bps higher than its closest peers in its retail bank. I believe that Wells can reduce expenses towards the levels of its peers over time, and even if it only closes part of the gap, the stock is trading at a large discount to the value of its significant earnings power.

We have owned shares for roughly two quarters, and during that time the business results have not been good. Our share of pre-tax pre-provision profit is down marginally over that time. The company depends to some extent on interest rates, and rates have moved against Wells since we initially bought shares. That, along with some conservatism in its loan book, has led to lower interest income and earnings.

On the other hand, Wells has been returning earnings along with excess capital to shareholders. After two quarters of owning Wells, we own roughly 8% more of the bank due to share repurchases and dividends that we reinvested. I expect that over the first two years of ownership we might own 30-35% more of the bank. As long as interest rates don’t move massively against us, we should do fine in this scenario as the earnings power stays intact. And if the company can turn around its cost structure, the resulting strong earnings should generate excellent returns for us. As opposed to our other investments, where the businesses are already doing well, this situation could, and most likely will, take a few years to play out.

Summary

Most of our companies have grown their intrinsic values in the range of 10-15% over the past couple of years. Transdigm has been temporarily above that, due to the Esterline acquisition. Wells Fargo, on the other hand, has grown below that rate and will likely continue to do so for some time.

Importantly, our above average investment returns over those two years have been directly driven by these excellent business results. I hope that in the future these businesses can increase their intrinsic values in the range of 10-15% per year, which over the long-term should make us a similar investment return.

Future Outlook

After such a strong year, I think it’s important to set expectations. We own what I consider to be a group of high quality businesses that are creating value and growing, but our returns this year (and over the past 5 years) have been significantly boosted by valuation expansion. Now, the majority of our investments trade above their average valuations over the past 5 or so years.

We do own some investments - Berkshire Hathaway, Magellan Midstream Partners, Enterprise Products Partners, and Wells Fargo - where the valuations look attractive, but the rest generally trade more expensive than normal. Transdigm trades at roughly 17.5x EBITDA while it usually trades around 15x, Brookfield trades at a premium to the sum of its parts while it usually trades at a ~10% discount, Constellation Software trades at ~27x FCF while it usually trades at ~22-24x, and even Charter trades a bit higher than usual. For all of these businesses, I think our returns over 5 or 10 years are very likely to be lower than the gain in intrinsic value over that time period.

Even though most of these businesses look optically expensive, I’ve chosen to hold our investments in them. I see a path to our target returns even while underwriting these businesses with conservative (i.e. much lower than current) terminal valuations. Holding expensive shares exposes us to significant risk, as valuations can revert downwards, sometimes violently. Our returns over the next month or year or two could be more volatile than if we rotated into cheaper investments. But I’m focused on our 10 year returns, and I see the highest 10 year returns in things like Constellation Software or Charter. As soon as that isn’t the case, we’ll move on.

Concentration Risk

Currently, I view concentration as the biggest risk that we face, since we only own 8 stocks, and I think it’s important to properly address this risk. With 8 stocks, if I make a mistake, our portfolio could lose 5% or more of its value relatively quickly.

The easiest way to address this risk would be to simply own more companies. We could be more diversified and also sell some of our more expensive stocks, rotate into cheaper things, and simultaneously solve our overvaluation problem. Unfortunately, I don’t see any investments I like as much as those we already own. If you made me buy 5 or 10 more stocks tomorrow, I believe the odds are high that I would actually be adding risk to the portfolio by buying worse businesses with lower expected go-forward IRRs. This is exactly the sort of behavior that I engaged in in 2017 and 2018, and I spent 2019 undoing these moves because I had taken too much risk.

In order to properly diversify, I would need to make investments in more good companies at attractive prices. I’m generally not seeing many of those opportunities, so I’m content to hold what we own. I would like to own more investments, but I don’t believe we need to own more investments. Owning 8 stocks seems like a terribly small number, but the important metric to me is business diversification - or diversification across business lines and end markets - and we have more of that than it first appears. For example, Transdigm makes parts for every important airplane, Constellation Software owns dozens of individual software companies, Brookfield Asset Management owns stakes in hundreds of different assets, and so on.

I could quite easily build a portfolio of 15 companies in similar industries to our current investments with far less true business diversification and more business risk. In fact, I think that if we put our whole portfolio into Berkshire Hathaway that there would actually be less long-term risk of losing money than we currently have or that many 20+ stock portfolios have. I will be monitoring our concentration and looking to make more investments where that makes sense, but I will not be making investments just to improve headline diversification metrics.

Conclusion

2019 was a good year for us, driven primarily by excellent business results at our portfolio companies - we made ___% on our stocks and __performed the stock market by ___%.

Looking to the future, I believe that things might look quite different than they’ve looked over the past few years - the economy has been strong for a long time leading to valuations that are generally high, and at some point both of those things will reverse. I’ve spent most of this letter detailing how we’re positioned, and I want you to come away from it with four main takeaways.

First, over time, our investment success will be primarily driven by the business results of our portfolio companies. Our success over the past two years is a direct result of our portfolio companies executing well. At the end of the day, if our businesses continue to perform well, our investments will perform well over the long-term, and vice versa. The rest is mostly noise.

Second, even though our returns are primarily a function of the growth of intrinsic value of our portfolio companies, it is important to understand that in some situations valuations can dramatically influence returns. Today, valuations look high, and it is somewhat likely that our returns will be a few percent lower than the annual gains in intrinsic value of our portfolio companies over the next 10 years. Importantly, I still see the potential to meet our hurdle rates even with lower terminal values.

Third, I have increased the average quality of our portfolio companies. I sold some stocks of obviously lower quality companies and redeployed the proceeds into higher quality companies that we already owned. Going forward, this should significantly reduce our long-term business risk.

Fourth, in an ideal world, we would be able to diversify by buying more investments. Given current high valuations, I don’t see opportunities to do that. I will be patient and won’t diversify just for diversification’s sake; instead, I will diversify when I believe that owning another company adds to the quality and safety of the overall portfolio.

In closing, my goal is to protect and grow your capital over the long-term. We won’t chase hot stocks or unprofitable companies. We’ll continue to invest in good companies at reasonable prices. If I can’t find these, we’ll be patient until I see the next opportunity. No matter what the future holds, I believe we’re well positioned to make strong returns over the long-term.

[jetpack_subscription_form show_only_email_and_button="true" custom_background_button_color="undefined" custom_text_button_color="undefined" submit_button_text="Subscribe" submit_button_classes="undefined" show_subscribers_total="false" ]