2023 Annual Letter

Dear Investors,

The stock market returned 25.8% in 2023. As a reminder, 2022 saw significant losses for US stocks, and most of 2023’s performance reverses those losses, with cumulative returns over those 2 years at 3.2%.

We had a good year in 2023, with our stocks up roughly __%. It was nice to be up so much in 2023, but similarly to the stock market, those returns mostly reverse 2022’s losses, with cumulative 2-year performance at __%.

In this year’s letter, I’ll review the drivers of our results over the past two years. As usual, I’ll also summarize our trading activity and the performance of the businesses that we’ve owned over time.

At the start of 2024, our portfolios are tilted more towards US government bonds (I’ll refer to these as treasuries for the rest of the letter) than usual, and to conclude the letter I’ll walk through my reasons for that decision as well as my outlook for future returns.

2022-2023, In Brief

I struggled in 2022, and in that year’s letter, I wrote the following:

“While it is true that the poor performance this year is less costly given our long time horizons, that fact is not a let-off. We are still worse off for me having made the decisions I did.

A few investments are down ~40-50% from my initial purchase price. Let’s just say for simplicity that I bought 1 share of something at $1 and it now trades at $0.50. If this is just a temporary blip and the price goes back to $1 relatively soon, then it is true that we didn’t lose any money. But if I had been more patient, I could have kept the money in cash, bought 2 shares at $0.50 each, and we would end up with $2 and a very nice gain.

At the very least, even if the current drops in prices on our investments are temporary, buying them at $1 and seeing the price drop to $0.50 is a significant missed opportunity. However, if the market is pricing the stock correctly and it’s truly worth $0.50, then that’s a bad mistake and we’ve permanently lost money. As I’ll describe in the next section, I believe that most of the companies that we’ve lost money in are still poised to perform well over time and that the prices will recover. I wish I’d been more patient in buying them.”

In 2023, we did recoup those losses and had some gains on top of that. Given this recovery, those mistakes from 2022 generally fall in the “missed opportunity” bucket instead of the “bad mistake” bucket. While I am disappointed to have not fully seized the opportunities presented last year due to my early buying, I am glad to have navigated the past two years relatively successfully with some slight gains and outperformance.

Trading Activity, Our Current Portfolio, and Business Performance

There was slightly more activity in our portfolios last year than normal – there were two complete sales of our investments, lots of partial sales, and one large new investment.

The two complete sales were in Radius Global Infrastructure and First Republic Bank. Radius Global was acquired by a private equity firm, and we sold our shares for a small gain. I covered the situation at First Republic here for those of you who would like to review it.

Quick note: I sold First Republic for almost all of you before its stock fell precipitously in March of 2023. The reason that a few of us still held it was tax-related, as the stock that I kept was in accounts with high tax rates, and I didn’t want to incur a large gain on a sale. I only sent that write-up to those of you that still owned the stock at the time that it dropped, so if you didn’t initially receive it then you weren’t impacted by the sell-off.

I made one large new investment this year, which was into a group of companies that sell tools used in the manufacturing of a specific type of prescription drugs. We bought stock in Danaher, Thermo Fisher Scientific, and Sartorius. This investment follows a pattern that has worked well for us historically – these companies saw a contraction in revenues and profits in 2023 due to well-understood, temporary, cyclical factors. There are no new major worries about their competitive positions, their ability to generate profits, or their ability to grow over time. Many investors in the public markets cannot, for one reason or another, stomach poor short-term business results and the ensuing volatility in stock prices. This aversion to losses led to selling pressure and stock price declines to levels below what I considered to be fair value. I don’t know when exactly their businesses will recover, but when they do I expect that we will make strong returns on these investments. I’ll have more to say on these in future letters as our ownership period extends past a few months.

The last group of trading activity was to partially sell, or trim, many of our existing investments. I’ll cover this activity in more depth later in the letter, but for now I’ll summarize these trims by saying that I think it’s prudent to reduce our position sizes in most cases when stocks rise from a level that I think is undervalued, as they were at the end of last year, up towards what I believe they’re worth, as they are now.

Let’s now take a look at the businesses we have owned over time, their results for the year, and how that performance impacted the returns for their stocks.

Our largest position, Constellation Software, was up 63% in 2022. Constellation continues to consistently execute its playbook of running its large stable of software companies well, generating ample cash, and using that cash to acquire more software companies and drive earnings growth. We have owned Constellation for 6 years and its earnings have grown 21% per year over that time frame.

Transdigm’s stock returned 67% this year as the company continued to execute well and capture incremental volumes and profits from the continued global travel recovery. Its earnings in 2022 were above its pre-pandemic peak, even with sales volumes still below peak levels, and the outlook over the next few years is strong as travel continues to grow at elevated rates as it normalizes towards its pre-pandemic trends.

Amazon had a good year this year, as it made significant progress in better aligning costs in its retail business to current levels of demand, which has led to a sharp increase in profitability. While AWS’s growth rate is still relatively low due to customers rationalizing spend, growth appears to have bottomed and should reaccelerate in the future. Outcomes for both of these businesses were better than the market feared at the end of last year, which sent shares up 81% this year.

Similar to Amazon, Google’s stock saw a large return of 59% this year as its results came in better than feared at the end of 2022. Google’s core business grew, and that growth accelerated throughout the year. Additionally, the company showed significant cost control, which reversed the weak margins from last year and a major cause of the stock’s weakness.

Charter, put simply, continues to struggle. Last year I noted that the company is facing increased competition, which has slowed its growth and led to more uncertainty as to its true value. Not much has changed in the last 12 months – it has grown its earnings and subscriber counts slightly although it is clearly feeling the effects of that increased competition.

While I wish there could be a quick resolution here, the truth is that business results aren’t always linear or easy. While the future is more uncertain at Charter than at our other investments, its valuation is much cheaper. There is uncertainty and risk in every potential investment. My job is to only own an investment when the risk/reward skews favorably and to diversify enough that a bad outcome in any one place doesn’t ruin the whole portfolio. I believe the current risk/reward here is, in fact, quite favorable, but I’ll continue to closely monitor the situation to make sure that our entire portfolios aren’t harmed too much if some of the risks play out.

Berkshire Hathaway returned 15% this year as the company continues to create value consistently and conservatively. Berkshire should continue to be a relatively safe way to make a good long-term return.

Going through some of our smaller investments, Visa and Mastercard continued their steady growth in revenue and earnings and the stocks returned 26% and 23%, respectively. S&P Global returned 33% as the outlook for the economy, and therefore its core credit ratings business, improved. Microsoft started the year at a relatively low valuation, had an excellent year, and has enjoyed a 58% return due to strong profit growth and multiple expansion. Salesforce is up 25% from our purchase price as it has continued to grow at a decent rate and more importantly has exhibited strong expense control and margin expansion. Enterprise Products Partners had another profitable year without much of particular note and returned 18%.

Our Portfolios – Less Invested In Stocks Than Normal

When we net out the trading activity for our stocks in 2023, I sold far more that I bought, so to begin 2024, our portfolios are much more heavily tilted towards treasuries than they have been historically.

For most of the time that we’ve been investing together, our accounts, when considered in aggregate, have been roughly 75-80% invested in stocks and 20-25% invested in treasuries.

To start off 2024, our accounts are worth $___mm in aggregate, with $__mm of that total invested in stocks and the remaining $__mm invested in treasuries. Stocks make up roughly 60% of our total assets, down significantly from our historical positioning.

In these letters I usually focus on developments at the businesses we own, as those will be the primary determinant of our returns over time. However, equally as important to our long-term returns is our allocation between stocks and bonds. Given that we own much less in stocks compared to normal years, I want to spend the rest of this letter talking through how I think about that decision.

Stocks vs. Bonds – Household Level Considerations

I invest money for roughly 60 households. In the previous section I talked about our holdings as a whole, but in reality, there is significant variation from household to household, as our financial circumstances and goals are quite diverse.

In general, those of you with relatively long time horizons for your investments will have more of your assets invested in stocks than those of you with relatively shorter time horizons. “Time horizon” is not necessarily a euphemism for age, as “short time horizon” can just mean that you may have a productive use for your money relatively soon, whether it’s for retirement, a house, or anything else.

We have now been investing together for 11 years. We have generated quite strong returns through a combination of a large allocation to stocks, a period of strong returns for the stock market in general, and roughly 2% / year of outperformance for our stocks above the index.

For a decent number of you, those returns mean the assets you currently own are enough to do all the things you want to do, and it would be foolish to risk that security for any reason. It is always important in investing to remember what our individual goals are, realize when we have reached those goals, and subsequently solidify the foundation that we have built.

If that describes you, then as we continue our investing journey together, the focus will be firmly on the preservation of the value that you, through hard work and diligent saving, have already created. This will naturally mean, in most market conditions, a higher allocation to lower-risk investments like treasuries.

For those of us that are still in growth mode, it is business as usual, and we will likely continue to hold the majority of our accounts in stocks. The exact breakdown between stocks and bonds will depend on how much you are consistently saving, with a higher savings rate leading to a higher allocation to stocks, and the number of attractive opportunities available in the market.

Stocks vs. Bonds – Individual Stock Considerations

To me, the core tenet of investing is that, if you are going to take risk, you need to get paid a commensurate return for taking it. As I write this, we can invest our money in treasuries and make a risk-free return of roughly 4-5%. If we are going to take more risk, whether that means owning corporate bonds or equities, our expected return for making a potential investment needs to be higher than that available from treasuries so that we’re compensated for the extra risk that we’re taking.

It doesn’t pay to be too scientific about this, but in general I would say that in order to be compensated for the risk of owning stocks, you should be able to expect returns that are at the very least 3-4% per year higher than the risk-free rate, or if the risk-free rate is very low, then 8% at a minimum. All estimates are uncertain, but I do my best to be conservative and look at potential returns over 5-10 years when I do these calculations.

When I looked at our stocks at the beginning of 2023, I thought that many of them were offering returns over 5-10 years of roughly 10-15% per year, which was a very high spread to the 4% risk-free rate at the time, easily clearing the incremental 3-4% hurdle. We had been consistently buying stocks up to that point and had a large allocation across accounts.

With such a strong year for our stocks, the valuations of almost all our investments went up significantly. If I do the same calculations today, it’s difficult to see more than perhaps 8-10% per year, which is getting close to the minimum return I’m willing to expect in order to take equity risk.

Amazon is a good example of this dynamic. Last year the stock closed at $84 and I argued that I thought it was worth around $140-150, which is the price from which I think you’d make roughly a 8-9% return. The company had a good year operationally, and at this point I believe it’s worth around $150-165. But the stock ended the year at $152, so it’s close to my estimate of its value.

Most of our stocks, in a similar way, outperformed the growth in the intrinsic value of the underlying businesses, and most of them moved towards prices where if I look forward, I see reasonable returns of perhaps 8-10% instead of great returns of 10-15%.

Lower expected future returns make these investments definitively less attractive. All else equal, I would prefer that we own less of things as they become less attractive.

A further consideration is that as a stock goes up, it becomes a larger and larger portion of our portfolios. I prefer to own less of it, but if I do nothing then we own more.

In the past, I had often let these investments ride. Sometimes that was because of tax considerations, which do complicate the calculus. But other times I admit that I could be too hands-off in managing the size of positions as they worked for us, letting them get too large even as the risk / reward deteriorated.

Two of my recent mistakes, First Republic Bank and Charter, were the result of large winners becoming positions that were too large and not taking enough action to reduce their size. I ended up being wrong about those businesses, and the combination of relatively large positions, full valuations, and my miscalculation of the businesses meant that we lost more money in those stocks than we should have.

Going forward, one way to remedy this is to be a little quicker to sell at least some of our investments as they go up towards my estimate of their fair value. That way, the exposure won’t be so large that if my estimation of the business’s prospects is incorrect, we’ll incur significant losses.

As most of our stocks performed very well last year, I have actively trimmed the size of those positions for the reasons mentioned above. I made these decisions based on the merits of each individual stock, but in aggregate it has led to a lot of selling.

Importantly, I do still think the returns from the stocks that we still own will be satisfactory. As mentioned above, my best guess is that the group of stocks we own could make ~8-10% per year over time, of course with uncertainty around that estimate from a large variety of factors. Given that the returns I expect are materially lower than they were last year, although still adequate on an absolute basis, it is just my preference that we own less of them than we did one year ago.

As I’ll discuss in the next section, valuations for the stock market as a whole look quite high. That environment has made it difficult for me to find new stocks to buy, so all of the selling without buying to counterbalance has resulted in higher balances of treasuries than normal.

Stocks vs. Bonds – Environmental Considerations

I thought it would be helpful to include a few charts that help to show the state of the current environment we’re in. These charts help answer the question posed above of – will I get paid a commensurate return for taking on extra risk if I own corporate bonds or stocks instead of treasuries?

The first chart shows how much extra yield an investor will receive if they own BBB rated corporate bonds. These are relatively safe investment-grade bonds that don’t default very often. The extra yield over treasuries is mostly a function of the market’s risk appetite. A lower yield means investors are accepting lower returns to take on credit risk, and a higher yield means investors are demanding higher returns:

As you can see, investors are getting paid very meagre returns for taking on credit risk in today’s environment.

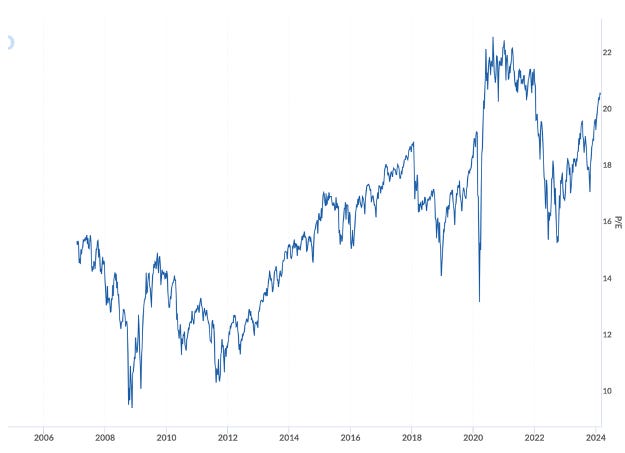

This next chart shows the price / earnings ratio for the S&P 500. In general, a higher P/E ratio means stocks are more expensive and market participants are more optimistic, demanding lower returns than normal in order to hold stocks. As of today, stocks are more expensive than at any time over the past 20 years, excluding the brief period in 2021 when they were trading at very elevated levels.

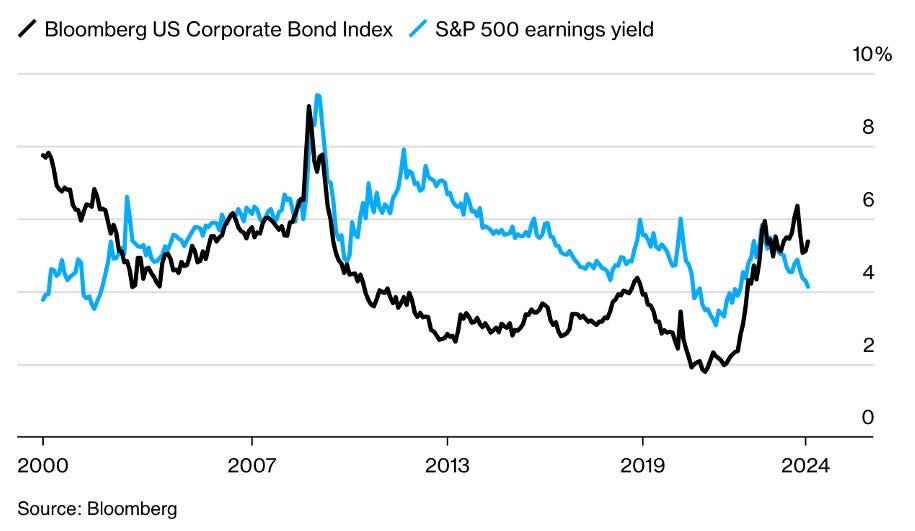

The last chart shows the yield you are expected to receive if you own stocks. This is presented as the “earnings yield” or, mathematically, earnings / price, which is the inversion of the chart shown above. The chart then compares the earnings yield for stocks to the yield you can receive if you own corporate bonds.

Given that stocks’ earnings grow and bond payments don’t, it isn’t as simple as “whichever yield is higher is more attractive” but in general for stocks to be attractive you’d want the earnings yield to be higher than corporate bond yields. As the chart shows, currently the yield that equity investors receive is lower than the yield on corporate bonds, and on a relative basis to bonds, equity yields are much lower than they’ve been over the 11 years that we’ve been investing together.

Not Chasing Returns

To summarize the above sections – we are currently holding much more of our assets in treasuries than normal. Part of the reason is that some of you have reached your financial goals, and we’re much more focused on preserving that wealth. Another part is that most of our stocks have moved up from undervaluation towards fair valuation, leading to net selling of equities in your portfolios. Last, the general market environment is such that investors are generally not getting paid much for taking risk, which has made finding new investments difficult.

Given these factors, what are we to do?

The first option would be to sell more of our stocks, even though I think the returns on those individual securities will be strong, because the stock market generally looks expensive. This is never how I have operated, as I always believe in making decisions on a stock-by-stock basis. The companies we own are strong, performing well, and trade at generally reasonable valuations. If the valuations keep increasing we will likely keep selling more piece by piece, but as of now, I see high enough returns to keep owning our current positions.

The second option would be to hold our noses, invest in my next best ideas in the stock market or perhaps some higher yielding corporate bonds, and hope that even though those incremental opportunities aren’t great that they’ll work out at least satisfactorily.

The third option would be to let our treasury bond balances continue to accrue and only invest them into stocks when there are more great opportunities to be had.

In choosing between options two and three, individual attitudes obviously vary, but my guess is that most of you generally have a negative reaction to owning less stocks than normal. I think that’s a normal reaction, especially when it has felt soooo easy to make lots of money owning US stocks.

Given how strong the returns have been over time, many people think it’s irresponsible not to pile as much money as they possibly can into the US stock market. I have a slightly different view, which is that sometimes US stocks are priced richly enough that a reasonable estimation of the future suggests returns that aren’t materially higher than treasury bonds.

I believe that we are in this environment today, which is why I haven’t rushed to buy more stocks in your accounts – I have chosen option three. Let’s take a look at the historical record for equity investments, which is what most investors use to claim you must always be fully invested in stocks, with a little more rigor than is commonly used.

Over the past 11 years that we’ve been investing together, the US stock market has made 13% per year, which turns $1 of initial investment into $3.70. If we zoom out, US stocks have gone up at a strong rate for pretty much the whole time any of you have been involved in financial markets. The last time that US stocks didn’t do well over an extended period ended in the early 80s, when some of you were just starting your careers. If we go back even farther, over the past 100 years, US stocks have made ~9% per year, which turns $1 of initial investment into roughly $5,500 of value today.

In short, if you have been a US based investor, and you haven’t been almost fully invested in US stocks, you’ve made much less money than you could have. That has conditioned most people to think that investing in stocks for the long-term is always the right decision.

I generally think that investing in stocks is a great way to try to build wealth over time. However, it is also my view that, instead of blindly extrapolating the historical record forward, investors need to think more critically about what has happened in the past and what might happen in the future.

If we re-examine the historical record with a broader lens, we see that equity investors don’t always make terrific long-term returns.

For investors based in the US, it’s easy to look at equity returns in the US and think that those numbers are what everyone earns, but if you want to look at the historical record of all equity returns, you need to look at all the equities, even the foreign ones.

If we re-examine the historical record looking at foreign returns, we see a much different picture. Over the last 11 years, foreign stocks made 4% compared to the 13% for US markets. An interesting finance paper shows foreign equity returns of 5.0% annually for the 50 year period of 1970-2019, which is not only mediocre in an absolute sense, but also falls short of the 5.1% annual returns for foreign government bonds.

Remember, this 50-year period encompasses the time when humanity has had the most progress on almost any important metric in its history. Technical progress has been astounding, capitalism has proliferated across the globe, and we haven’t had any destructive world wars. Even with all of this progress, if you didn’t own US stocks, you would have done better owning government bonds.

The US, when you stop to think about it, is quite a special case – it is the largest power in the world, it has generally strong enforcement of property rights, it has low inflation, it has birthed most of the world’s most important companies, and its companies have mostly been run for the long-term benefit of shareholders.

We may not want to assume that this special case will always be repeated or that this means that owning equities is destined to vastly outperform owning bonds. Instead, we might want to think of the last 100 years of wealth creation for equity holders in the US as something of a miracle. I do believe that the US is the best place to invest and that the US will continue to create wealth in the future, but I do not believe it is prudent to plan your financial lives on the assumption that US stocks always go up over time no matter what.

While the factors that led to success over the past 100 years are generally still present, it doesn’t mean US investors are destined to make 9% per year over time. There are many risks, big and small, that will lead to different results. Strong investment returns aren’t achieved by looking in the rear-view mirror and assuming everything repeats.

Financial markets are complex, and they generally adapt to conditions over time. The stocks of companies in attractive countries like the US will generally sell for much higher valuations than those with less favorable attributes. These higher valuations often make sense, but that can also mean that if conditions change for the worse that investors might earn very poor returns.

With these ideas in mind, and a clearer sense that equity investments in any country are risky over time, we come back to the most important question from the previous section – if we invest our money in equities, can we expect to make enough of an incremental return over risk-free government bonds so that we’re being compensated for the extra risk we’re taking?

I will spare you all of the arithmetic, but if you assume that US corporations enjoy the same revenue growth over the next 10 years as they enjoyed over the previous 10; if you assume profit margins, which are currently at all-time highs, stay at current levels; if you assume that equity valuations, which are also near all-time highs, stay at current levels; and if we don’t have any negative surprises on interest rates or corporate tax rates, then you might make something like 7-9% in US stocks over the next decade.

That is an okay premium to the 4% you can make in treasuries, but that assumes everything goes perfectly. There is very little margin for error if you own stocks at these levels, and there are very many opportunities for errors.

I feel very strongly that investors do not need to rush into stocks right now. Valuations are high, and we’ve seen that equity investors are not destined to always make very high returns no matter the conditions. We can continue to be patient and wait for better opportunities.

Optionality

For the reasons listed in the preceding sections, it makes plenty of sense to own more treasuries than normal. But there is one additional, very important aspect to this decision that falls outside of the analysis of likely returns of stocks and bonds - owning a large amount of very safe assets means that volatility will likely increase your returns.

Owning a large amount of treasuries will obviously lead to good results for us if stocks do poorly over the next 5-10 years, but even if US stocks do relatively well over that time, an investor with a large amount of treasuries can do quite well if there’s even 1 or 2 bouts of higher volatility and lower market prices.

If you look at US markets over the past 10 years, a time when they posted abnormally strong returns, there were a couple of large drawdowns that provided opportunities across the board – one during COVID in 2020 and one as interest rates increased in 2022. Clearly, investors with large treasury holdings could take advantage of these opportunities.

Even more importantly, however, there were plenty of good opportunities in more isolated sectors when the whole stock market wasn’t as weak – industrial companies in the beginning of 2016, software and growth stocks at the end of 2018, and many value stocks in the fall of 2020. Investors with access to cash could put it to work at great returns during any one of these times, even if the stock market was not trading too weakly.

For our relatively large cash balances to serve us well in the future, we only need 1 or 2 opportunities like this in order to deploy our cash balances at very strong returns. You can never predict exactly what will happen in financial markets, but you can be sure that in any given sector, when the future starts to look a little scary, prices will come down significantly and investors with access to cash will have opportunities to make investments at attractive valuations. When you have cash, volatility is your friend.

Outlook

While predictions are difficult, I am comfortable saying that we should all be expecting forward returns lower than the ~14-15% per year we’ve generated on our stocks historically and the ~11-12% we’ve generated on our whole portfolios. This is not any great tragedy. We have been blessed with a very good environment over our first 11 years, and we capitalized on that, made very strong returns, and grew our wealth at a high rate. But things aren’t always, or even often, that easy. It’s normal to have more difficult environments sometimes.

While I believe that our strategy will generate good results, and while I like the investments that we do own, they aren’t as cheap as they were last year. If we simply held everything we own today, it will be difficult to generate portfolio-level returns of much more than 5-8% per year over the next 10 years. Our large treasury holdings will limit our returns on that money to 4-5% per year, and given relatively high valuations on the stock market, I think it would be difficult for us to make more than about 8-10% on our current equity portfolios over that time.

That being said, our portfolios can and will change over time. We are likely to get some good opportunities to sell our treasury bonds and invest the proceeds into stocks at high returns. Financial markets rarely move in straight lines, and we’re positioned to benefit strongly from any weakness.

For now, we will wait. The main reason I struggled in 2022 was because I was impatient in 2021 and chased some investments that I shouldn’t have. I’m loathe to repeat that mistake, especially after an 11 year period where we have generated such strong returns and have built our wealth into strong positions where most of you don’t need to take much risk to achieve your goals. We can afford to be a little more conservative than normal.

Conclusion

We had a good year in 2023, reversing our losses from 2022 and making some incremental returns above that. It caps off a strong first 11 years where we have made strong gains in our portfolios by being invested almost entirely in equities.

Looking forward, given an environment where valuations are relatively high, we should all expect to make lower returns in the future than we have in the past. With conservative positioning and large balances of government bonds, we can welcome the ensuing volatility that is likely to come our way, and if things get difficult, we can put that money to work at good returns and drive continued strong results into the future.