The Case for Berkshire

My last post on Berkshire was a bottom-up, technical valuation that found that the current market price, which stands right around $200, is likely to produce returns in the range of about 10% annualized. In this piece, I want to take a hard look at all the risks that investors face when they invest in a company and how those risks present themselves in relation to Berkshire. We will see that the company is so diversified, run so rationally, and financed so conservatively that the case for Berkshire rests in the ability to make a good return while avoiding vast swaths of the risks that investor normally face when investing in a stock.

Disclosure: my clients and I are long Berkshire Hathaway.

Thinking about Risk

When I’m thinking about risks in general for any stock, I think about four main buckets - competitive risk, execution risk, capital allocation risk, and capital structure risk. We’ll discuss each in turn as it relates to Berkshire.

Competition

This is the main risk that people think about when investing in a business. What are the odds that a business loses its customers and earnings power? Investors worry about technological disruption, more intense competition, regulatory change, less demand, and on and on and on. I can think of 100 competitive risks for any company that I own. We have all seen the statistics on how many companies in the Dow have gone bankrupt over the last 50 or 80 years. Capitalism is brutal and it kills most companies sooner or later.

Berkshire obviously faces these risk in each of its business segments, but the company is so diversified that weakness in any one business segment doesn’t do much to the whole. I remember Munger saying a few years back that “we won’t win every brand skirmish” in response to a question about one weak segment (it might have been Fruit of the Loom). What’s important is that Berkshire doesn’t need to win in every business. It feels good to be a shareholder and not worry that a change in the competitive environment in one specific industry will have a large effect on your long-term returns.

We can actually see this principle in action looking back at Berkshire’s historical results. The industry that has been toughest over the last few years for Berkshire is probably reinsurance, which used to be the most important industry to the company. How has Berkshire done in that time? Intrinsic value is still up at a 10% annualized pace almost no matter the time frame you look at it over the last cycle (i.e. starting at some point during the expansion in the mid 2000’s), even though one of its most important industries has been a poor performer. What other company can you say that with?

Contrast this with Markel, which I admire a lot and in my opinion is one of the best run companies out there. Markel has a large reinsurance operation which has faced the same tough reinsurance market and super low interest rates. Intrinsic value creation has been pretty poor over the last 5 years or so almost entirely due to a tough environment. Markel management has actually done quite a good job through that time, but since it isn’t as diversified as Berkshire is, the results haven’t been nearly as good.

Last, it’s comforting that the biggest businesses are probably Berkshire’s best. By market value the most important ones would be BNSF, Geico, Precision Castparts, Berkshire Hathaway Energy, and the banks. These are all fantastic businesses and I would be surrised if any of these wasn’t earning more money in 10 years than it is now. I’d be a bit more worried if Berkshire’s biggest business was NetJets or something, but the big ones tend to be the good ones.

As shareholders, we know we’re diversified to the extent that difficult environments in even the most important industries won’t unduly hurt the performance of the whole. We also know that Berkshire’s big businesses are generally its strongest.

Execution

Poor execution is probably the second biggest risk for investors. Almost any business can be mismanaged to the point that its value is severely damaged.

The causes of mismanagement are quite wide ranging and not always controllable. You can’t say that every Berkshire business is managed expertly, because they aren’t. That being said, the company has two huge advantages in this area - Berkshire judges managers on long-term performance and compensates them like owners.

Investors can think of a huge number of instances where managers are paid when the stock goes up over a short time frame. Unfortunately, that’s the status quo and also the worst way to incentivize executives to run a company. Executives know they can’t invest for the long-term because that will depress profits and the stock price, even if they know that that’s the correct long-term move.

With Berkshire, we know that managers are given lots of autonomy and are incentivized to grow intrinsic value over the long-term. Again, that doesn’t mean that every manager will be a superstar, but I think it does cut out the biggest controllable factors that negatively affect performance. If this structure remains, we can reasonably expect that on average Berkshire should be better managed than the average public company. Since Berkshire owns so many companies, we also remove a lot of the risk of having a good structure but having a bad result because we were unlucky with a manager in one business unit.

Capital Allocation Risk

The next big risk is that a company mis-allocates its earnings. Obviously, Berkshire has been incredibly successful in large part due to excellent capital allocation. But we all know that Buffett is old and he won’t be there forever. Can we be sure that capital allocation will be prudent going forward? I think so.

First, and most importantly, I firmly believe that capital allocation is a skill that can be taught and retained over time. I honestly don’t believe that it takes a genius to avoid buying back stock at clearly elevated levels or to skip an acquisition that’s way overpriced. It takes a culture of actively looking at the expected rate of return on that investment, using sober assumptions, and doing whatever makes the most sense. The math isn’t that hard. The discipline is. If you have a culture that praises discipline with shareholder funds, then you are way ahead of the competition.

Berkshire’s culture is laser focused on finding the best returns with its money, and it has a team of people who understand risk and are excellent capital allocators. I believe that the odds that they are proficient capital allocators over the next 20 years are incredibly high.

Furthermore, all you really need is for the capital allocation to be just okay. The current size of the company means that there’s no way that Berkshire will be deploying its capital at 15% rates of return. From the current price, you just need to avoid big mistakes. Even if Berkshire allocated all of its capital at an 8% return over the next 10 years, if the businesses they currently own perform like I expect, the value of the whole company would grow around 9% per year. That’s a perfectly acceptable result.

To have the performance of the whole company be materially lower than 10%, you would need the return on incremental investment to probably be at 5% or lower. Do we think that will happen? Probably not. They will most likely have $200-300 billion to allocate over the next 10 years. If you’re avoiding the big tech stocks and the IPO’s, you’re not going around offering 30% premiums for companies that trade at 52 week highs, and when you purchase individual stocks you limit yourself to 10% of the shares, then could you even deploy that much money? I honestly doubt it.

Then how will they deploy the money? My guess, and what Buffett has said, is that they’ll start to repurchase significant amounts of Berkshire stock. Over the last 10 years Berkshire has traded at a noticeable conglomerate discount (i.e. at a discount to the value of the sum of the individual companies that Berkshire owns), which means that at most points Berkshire can spend money to buy back its own stock at a discount. Since they’re rational capital allocators, as the deployable cash flow grows, I believe it will certainly be a rational decision to buy $10-20 billion of Berkshire stock per year because the opportunity set of other things they’re naturally interested in is quite low, as mentioned above. If they pursue this course, they’re likely to make those ~10% returns on the repurchases that I’ve mentioned.

All Berskhire shareholders need in order for a good investment result is for decent capital allocation. With the culture of rational capital allocation and a high likelihood for a cheap stock over time, Berkshire should clearly be able to clear that bar.

Capital Structure

This is a huge risk for any company and one that I think can be easily looked over by investors, very much including myself. Berkshire is very likely to do well over time, as we have shown. Sometimes, however, good businesses are ruined by over-leveraged capital structuresand/or a lack of liquidity. A six foot person can drown in a river that’s five feet, on average, as Buffett likes to say.

The relevant question to ask about the capital structure is whether anything could happen to make the company run out of either cash or borrowing capacity. We’re not thinking about long-term value. We’re thinking about short-term survival. What you hope to see is low debt levels, long-term debt as opposed to short-term debt, strong and consistent earnings, and low levels of other financial liabilities that ideally are matched with appropriate assets.

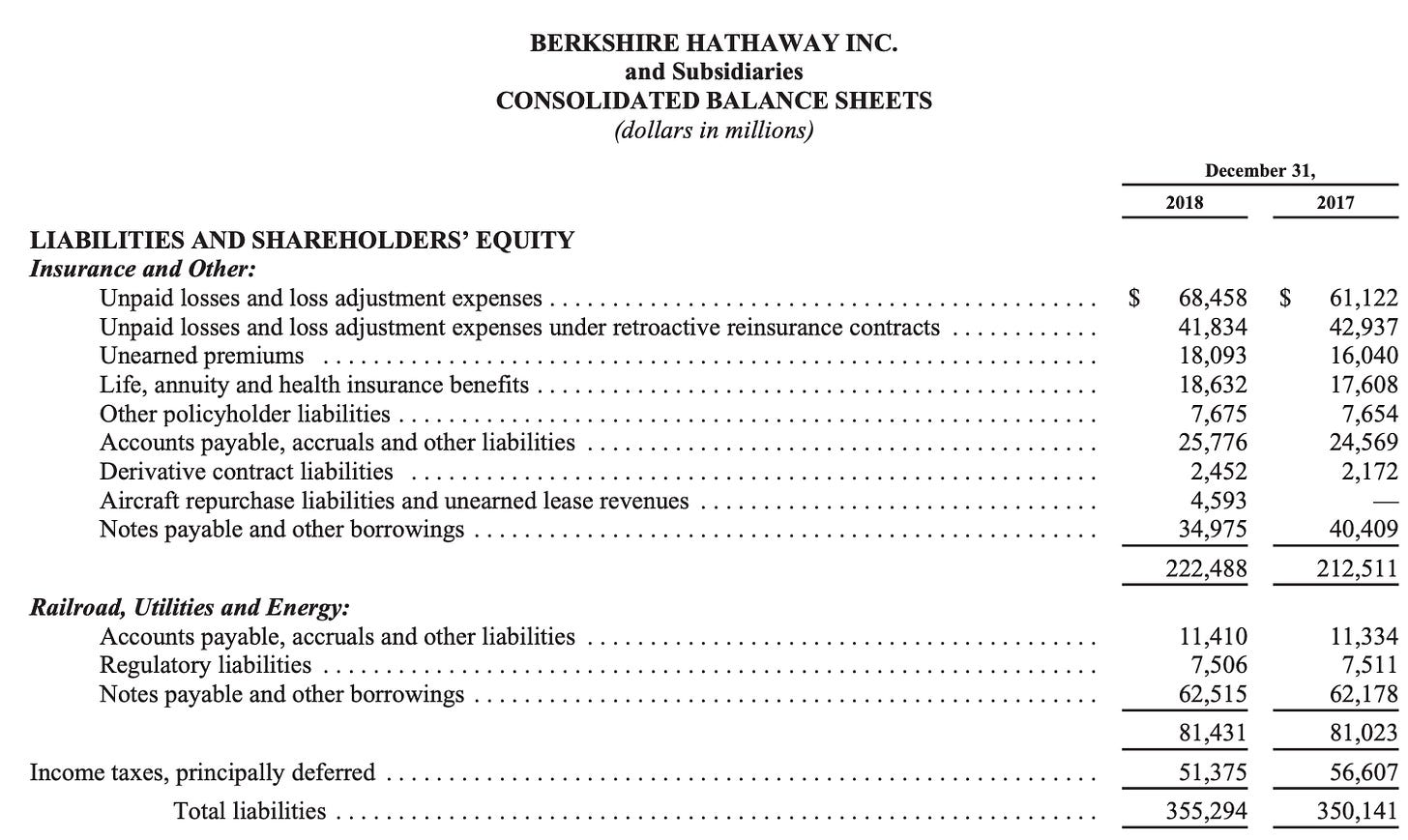

I’m going to spend a lot of time here going through the liabilities line by line, as I think it’s important to understand just where something could go terribly wrong. Here’s a look at Berkshire’s consolidated liabilities:

The first section holds Berkshire’s insurance companies and its operating business excepting Berkshire Hathaway Energy and Burlington Northern Santa Fe.

The first five rows consist of Berkshire’s insurance liabilities. When you net the values out to some of the current insurance assets, you get to Berkshire’s insurance float of $123 billion. These liabilities are usually matched by short-duration fixed income assets. If, for some reason, Berkshire had to pay out a large amount of these liabilities tomorrow, it could easily do so by redeeming its fixed income securities, which are mostly invested in short duration treasury bonds. The safety of the assets that are matched to these liabilities means that Berkshire would be able to meet those liabilities no matter what.

Berkshire does have $25 billion of accounts payable, largely in its operating businesses. These payables, however, are more than matched by receivables. The company has quite a large net working capital balance in these companies, so I don’t worry about those liabilities either.

Berkshire has ~$7 billion between liabilities on derivatives and in its leasing units. These are both fairly long-term liabilities that would not run off quickly, so the company could use cash flows over time to pay these off.

I’m going to skip the actual debt for now and move to the liabilities of the Railroad, Utilities, and Energy segments. These businesses do have lots of borrowings, but they’re all non-recourse back to Berkshire, which means that if something bad happened to the businesses and they couldn’t repay the debt, Berkshire wouldn’t be liable.

Next is the deferred income taxes. This relates to two different sources. First, the taxes Berkshire would need if it sold stocks with embedded gains. You obviously only need to pay those liabilities if you sell the stocks, so there’s no possible way to have this become a funding problem since you have the cash from the stock sales. The second source of deferred taxes comes with certain businesses, usually the asset heavy ones, where assets are depreciated on a tax basis more quickly than on an accounting basis. Basically, you pay less than the full tax rate because you’re investing a lot in the business and you get a tax benefit for those investments. As long as you keep investing, you don’t ever pay this money, so we can think of it either as a perpetual funding source or one that would reverse very, very slowly. Again, we’re not too worried about liabilities that accrue slowly. Furthermore, a large chunk of these come from BNSF, which is non-recourse anyways.

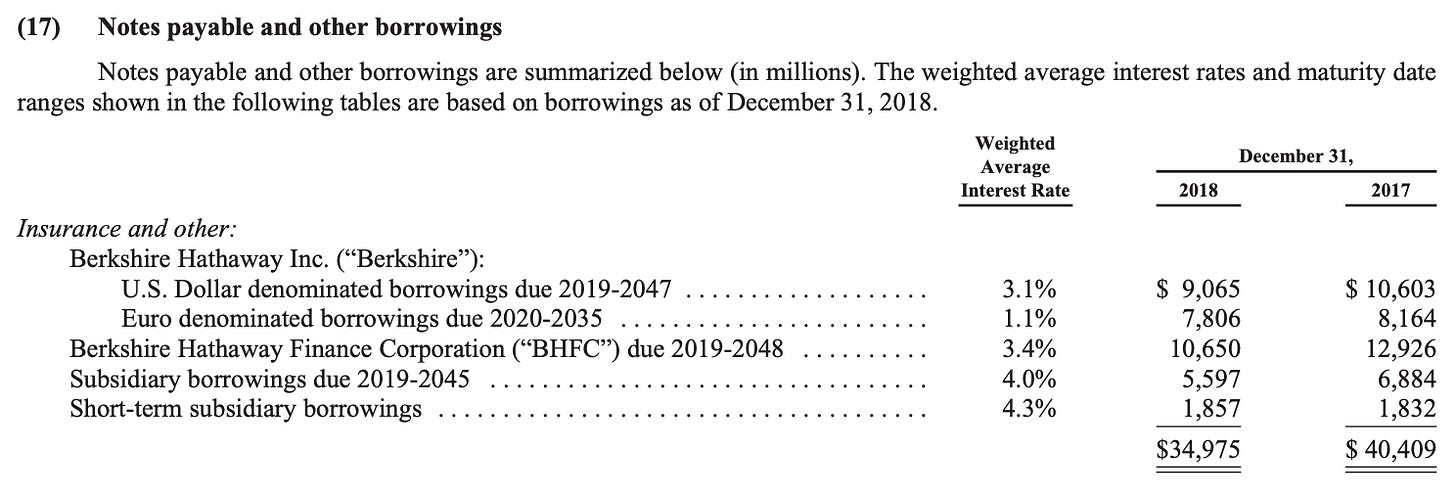

Last, let’s look at actual debt. We can see that Berkshire has ~$35 billion of debt. We can see a bit more detail here in the footnotes:

If we segment this out, we can see that these debt numbers are quite low given Berkshire’s size.

We could reasonably say that the debt of ~$17 billion issued by Berkshire itself could be allocated to the insurance segment, the $7.5 billion is allocated to operating subsidiaries, and the $10.6 billion is asset specific debt or part of Clayton Homes’ mortgage portfolio.

We can generally cross off the $10.6 billion as being worrying since that’s largely backed by specific hard assets or mortgages - if they need to pay the money back they can sell the assets. On the insurance side, a very conservatively run insurer would operate at a debt / equity levels of ~25%. With Berkshire’s ~$200 billion equity base on the insurance side, that gives us borrowing capacity of ~$50 billion compared to the current borrowings of $17 billion. For the operating subsidiaries, we could say that a 2.5x debt / EBITDA ratio would keep us squarely in investment grade credit ratings, which would infer ~$40 billion in borrowings compared to $7.5 billion of current borrowings, of which only $1.7 billion are guaranteed by Berkshire. Obviously, Berkshire has very low borrowing metrics compared to its size and earnings power.

We’ve now gone through all of Berkshire’s liabilities. What do we really have to be worried about here? The insurance liabilities are covered by short-term bonds and t-bills. No danger there. We have a large net working capital balance. We have some asset-based borrowings that would be paid off by selling the underlying assets and perhaps a bit of cash on top to make up the difference. The liabilities at the railroad and the utilities are non-recourse. The deferred taxes, if they’re ever paid back, would either be funded by the stock sales that cause the taxes, or in the case of the operating businesses, would run off gradually over time. The actual borrowings are completely miniscule compared to the company’s actual borrowing capacity, and not all of them are recourse back to the parent anyways. To top that all off, Berkshire generates $20 billion + of cash annually and holds tens of billions of dollars of truly excess capital in the form of stocks. It’s hard, if not impossible, to find a way that we run into a funding problem.

A Comparison to GE

GE’s current troubles give us an interesting case study into how things at Berkshire could go wrong. GE used to be perceived as one of the best conglomerates in the world and a true icon of American innovation. Now it’s being sold for parts and long-term equity investors have probably seen a permanent impairment in their investment. What happened, and could that happen to Berkshire?

Let’s go back through all of our big risks. Competitive risk, execution risk, capital allocation risk, and capital structure risk. The simplified story of GE is that it owned a couple of big businesses in segments that turned out to be more competitive than they thought (competitive risk), it owned one big segment that was enormously mismanaged (execution risk), it made a couple of disastrous acquisitions and bought back stock at elevated levels (capital allocation risk), and too much starting leverage brought a funding crisis after all these other problems surfaced (capital structure risk). They were four for four in all the things you don’t want to see.

The reason why the destruction of shareholder value has been so immense, in my opinion, is mostly due to the leverage, or the risk in the capital structure. Management has clearly incinerated quite a bit of value, but if they would have started out with conservative financing, the equity performance would have been much better - I would guess that the company might be worth 30% less than it used to be. Whatever the number, it would be well below the 70% that the equity has lost in the past couple of years.

But when these things happen and you’re at the limit of your borrowing capacity, you have a full crisis. The earnings are down so you need to pay off debt, but you have a $15 billion capital call in the insurance segment on top of that. The only way to generate the cash is to sell your best assets and dismantle the company. That’s much different than just seeing the value of the stock drop a bit while you work out the long-term problems.

Could something like this happen with Berkshire? We can concoct a scenario and see what happens. Imagine that BNSF’s earnings evaporated overnight, Berkshire wrote a bad insurance policy that cost them $50 billion, and we hit a recession and the company’s earnings power in its operating businesses dropped by half. Could all of this reasonably happen at once? Probably not. Call it the 1,000 year storm. Would Berkshire be okay even if it did? Almost certainly.

The BNSF debt might default but since it isn't guaranteed by Berkshire then the company wouldn't have to put any money up for that. Berkshire would have probably ~$50 billion of incremental borrowing capacity across its insurance and operating segments, as we found in the last section, and they’d still generate probably $10 billion of cash over the next six months. Berkshire could borrow some money, generate some more, and pay off the $50 billion liability.

They could also sell some of the equities they own if they wanted, but they actually wouldn't need to do that. That's pretty powerful for a 1,000 year storm. The price of the stock would clearly fall, but the company wouldn’t be imperiled. That’s the difference between Berkshire and GE. Berkshire’s value would go down but the company would keep its good assets and build value again over time.

Conclusion

In the first article, we found that Berkshire’s stock looks likely to gain in value somewhere around 10% over time. In this one, we took a rigorous look at the risks that face the company and found that in the big buckets, Berkshire is uniquely situated to withstand any risks that might come its way - it is so diversified that problems in one of its big segments wouldn’t affect the intrinsic value creation to a huge degree, it avoids the biggest structural problems in incentivizing management, it has a culture of rational capital allocation will most likely have a cheap stock to repurchase over time, and it is so conservatively financed that even in a worst case scenario across all of its business units at the same time it would still have liquidity to spare and wouldn’t need to further destroy shareholder value to save the company.

Berkshire is probably one of the least risky companies in the world in each of these individual respects. When you combine all of these attributes together, you get a company that probably offers the lowest chance of having a lasting, permanent impairment of your capital, and you can buy it for a price obviously less than it's worth. That's pretty powerful. That's the case for Berkshire.

Disclosure: Pursuant to the provisions of Rule 206(4)-1 of the Investment Advisors Act of 1940, we advise all readers to recognize that they should not assume that recommendations made in the future will be profitable or will equal the performance of past recommendations. This publication is not a solicitation to buy or offer to sell any of the securities listed or reviewed herein. This contents of this publication are not recommendations to buy or sell any of the securities listed or reviewed herein. Investing involves risk, including risk of loss. The contents of this publication have been compiled from original and published sources believed to be reliable, but are not guaranteed as to accuracy or completeness. Kyler Hasson is an investment advisor and portfolio manager at Delta Investment Management, a registered investment advisor. The views expressed in this publication are those of Kyler Hasson and not of Delta Investment Management. Kyler Hasson and/or clients of Delta Investment Management and individuals associated with Delta Investment Management may have positions in and may from time to time make purchases or sales of securities mentioned herein.

[jetpack_subscription_form show_only_email_and_button="true" custom_background_button_color="undefined" custom_text_button_color="undefined" submit_button_text="Subscribe" submit_button_classes="undefined" show_subscribers_total="false" ]