Wells Fargo: Poorly Managed, Still Too Cheap

Wells Fargo, long one of the most respected banks in the US, has had a rough past few years. The bank illegally opened unwanted accounts for clients in late 2016, and since then it has been repeatedly in the news for more mistakes and customer abuses. The operational performance has been so bad that in early 2018 the Federal Reserve took the unusual step of restricting Wells Fargo’s size. A year and a half later, Wells Fargo has not fixed all of the issues and is still subject to that asset cap. Disclosure: my clients and I are long Wells Fargo.

As things look bleak for Wells Fargo, the stock price has languished. Earnings are down from their peak in 2015, largely due to significant ongoing investments in compliance and controls. Shares trade around where they did towards the end of 2014.

While Wells clearly has problems, I believe banking is a fundamentally attractive business and Wells Fargo still has significant earnings power. With a cheap stock, I believe that the equity looks attractive for long-term shareholders.

In this post, I will outline why I like the banking business, examine Wells Fargo’s cost structure, find a valuation range based on whether or not they can fix their issues, and discuss some of the big risks to the investment. Although Wells Fargo has had significant problems, the price of the equity is simply too low and isn't accurately discounting the probable improvement in the company's cost structure.

Is Banking a Good Business?

When I look at any industry for a potential investment, I always want to be able to identify a reason those companies might be able to earn excellent profits over the long-term. The first question is usually, “is there some factor that makes the customers choose this company over its competitors that is not based on price?” If customers make their buying decisions based on price, that’s likely to be a poor business. If, however, there are other, more important considerations, then that business might be able to keep some pricing power and enjoy good returns on invested capital over time.

Banks have two main functions - gathering deposits and lending those deposits out. They make a profit as a spread between the rate they charge to lend and the rate they pay on deposits to borrow. Deposits are generally the lowest cost funding option for a bank, so a large deposit base helps a bank earn a good spread on its assets and liabilities. Most, if not all, of the good bank franchises have large deposit bases, so it’s vital that a bank can attract and retain deposits.

Let’s focus on those depositors as the “customers” and go back to the initial question - is there some factor that makes the depositors choose one bank over another that is not price related?

How did you choose which bank you use? For me, I’ve always banked with Wells Fargo. I’ve thought about switching, but my oldest credit card is through Wells, so if I switched to another bank and dropped the card I have it would hurt my credit score. It would also be a hassle to move and I wouldn’t get any more interest income on my deposits if I switched to JP Morgan or Bank of America. On top of that, the money in my checking account is a very small portion of my net worth, so a slightly higher interest rate wouldn’t even matter anyways.

What might prompt me to switch banks? The cause would need to be something service related. I, just like many Americans, barely ever go into a bank branch. I deposit checks into my account, transfer money electronically to my TD Ameritrade brokerage account to invest, and pay my credit cards electronically. Probably the only reason I would switch banks is if I couldn’t do any of those things seamlessly online.

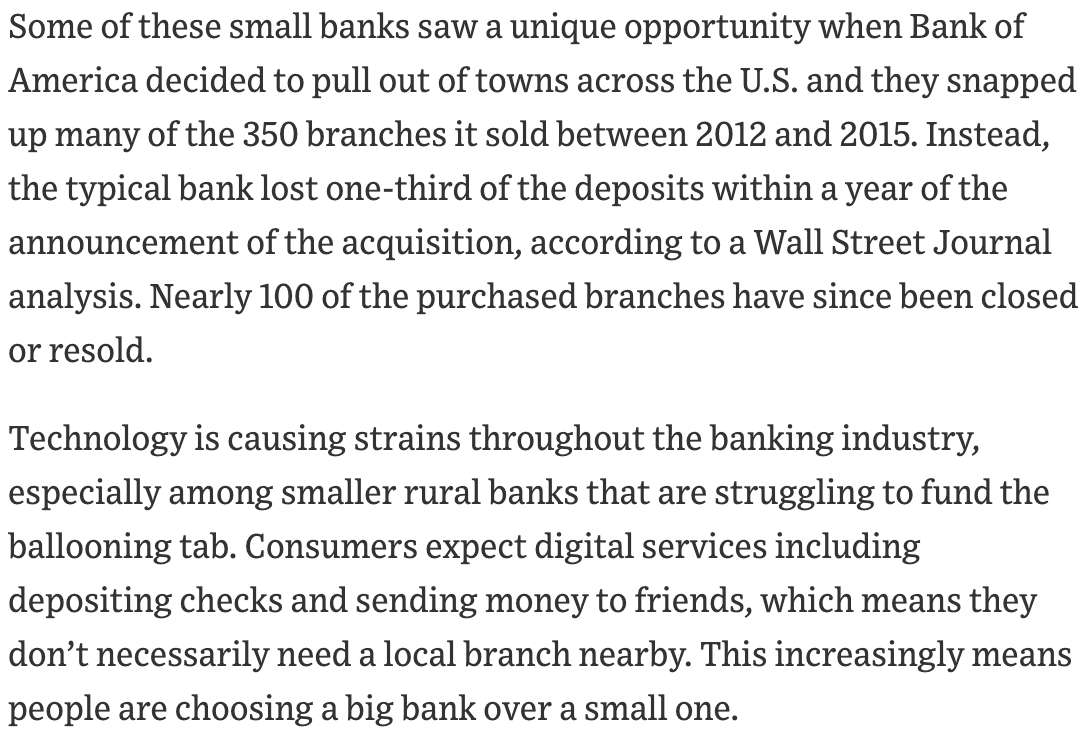

It turns out, many other people are just like me. Here is the only story I’ve recently seen where depositors left a banking institution en masse. What was the issue? A Bank of America branch turned into a small town bank branch, but that small bank didn’t have the technology infrastructure to make all of these banking tasks easy to do online, so half the depositors left in short order. Here’s the relevant passage:

Customers care about technology. If it’s easy to do everything they need online, then they’re generally pretty happy. There’s little reason to switch banks, creating a sticky deposit base. This stickiness allows banks to pay relatively little on their deposits, because customers generally care more about ease of use than interest income, or the price they get for the deposits. Low funding costs lead to high profit margins and good returns on equity.

Here’s one more anecdote on how sticky bank deposits can be. I was talking with a friend about a month ago and mentioned I now owned shares in Wells Fargo:

Friend: *eyes perking up* Why would you own Wells Fargo here after all the problems it has had?

Me: Wells Fargo has been inept at servicing clients, but banking is a good business and deposits are quite sticky. Wells has had more operational problems than you can count but has largely kept its deposit base.

Friend: A few years ago, I invested in a piece of investment real estate with a partner, and we banked the deal with Wells. After a few months, instead of sending the statements separately to each of us, they started to only send the statements to my friend’s address. I went into a branch but couldn’t get it resolved. A couple of months after that, they started sending my personal bank statements to my friend’s address. I went into the branch multiple times, but they still couldn’t get it right. Six months later, after threatening the manager of the branch that I would pull both my personal and business accounts (quite substantial in aggregate), they finally fixed the issue.

Me (presuming): Ha wow, that sounds terrible. So how is First Republic Bank treating you?

Friend: I still bank at Wells.

This is, of course, anecdotal, but I think it shows why banking is such a good business. It’s extremely annoying and difficult to move your accounts! It takes a long time to do all the paperwork, you have to re-do all of the auto pay features you’ve set up (and you might forget some!), and the benefits of switching usually aren’t even that high if you do go through all of the trouble.

A Quick Comparison To Insurance

I wrote two posts a few months ago about Markel, a large insurer and a company whose management I respect greatly. I came to the conclusion that I wasn’t interested in investing, and the reason was primarily because I think insurance is a tough business.

A quick comparison between insurance and banking will help show why I like banking so much. Both business, at their heart, make their money as a spread in income between their assets and liabilities. Although the mechanics are slightly different, they both involve pricing risk correctly.

But there is one major difference, and that is in the process of how these companies attract and retain their liabilities. We discussed the competitive dynamics for a bank - customers mostly don’t care about the price they receive for deposits, they generally just want to be able to handle all of their financial needs quickly and without friction. Once a customer deposits money into a bank, they usually keep it there for many years and sometimes for decades.

Insurers, on the other hand, attract liabilities by underwriting insurance business. How does an insurer win the right to underwrite insurance? Almost always by offering to do it at the lowest cost. Most individuals buy insurance based on what’s cheapest. Most institutions use brokers to help them find the best deal. If you do write the business at the lowest cost and win a contract, what happens the next year, when the policy needs to be renewed? If you try to raise the price too much, most people will again go out to get more quotes and switch if they can find a better price elsewhere.

Which business would you rather be in? The one where the biggest customer concern is a functioning app, or the one where brokers and individuals constantly go out and look for the lowest price and will leave you at a moment’s notice?

Is Wells Fargo Good at Banking?

For most of its history, Wells Fargo has been thought of as a well-run bank. The company has always had a low-cost deposit base, made sound loans, avoided the excesses of its peers, and printed profits. Wells Fargo behaved quite well in the lead up to the great recession and, different from its peers, arguably didn’t need the federal bail-out money that it was forced to receive. It has earned its reputation as a conservative lender.

However, as we discussed before, banking consists of both gathering deposits and loaning that money out. While Wells has been good at loaning the money out safely, the last few years have shown that they haven’t been gathering and servicing deposits in a fair, ethical way. The company instituted a high-pressure sales culture which led to employees opening fake accounts then proved itself unable to competently clean up the mess.

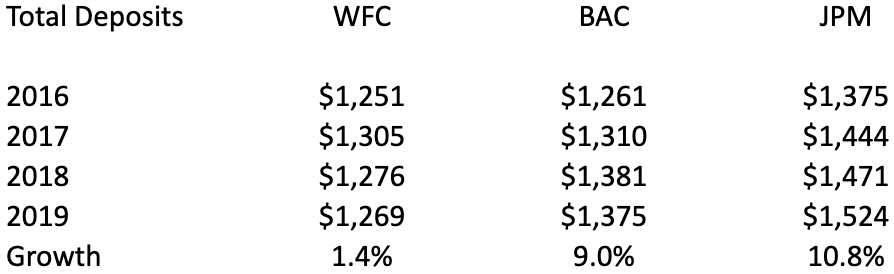

All of these mistakes have deservedly hurt Wells Fargo’s reputation. Here is a chart showing the company’s deposit trends compared to JP Morgan and Bank of America:

You can see how for two years after the scandal started, JP Morgan and Bank of America grew their customers and deposits at a much higher rate than Wells Fargo did. However, that trend has abated so far in 2019.

Wells Fargo has a lot of work to do to fix their issues. The company is spending many billions of dollars on oversight, controls, and compliance. However, it is notable that even with all of these problems, their customers have mostly stayed with the bank. As we discussed previously, people mostly only care about being able to get their banking done online. Not a lot else matters. While the scandal has clearly hurt Wells Fargo’s deposit growth, it has still kept its large, low cost deposit base.

The biggest impact of all this, so far at least, has been on Wells Fargo’s costs, which we’ll examine in the next section.

The Cost Problem

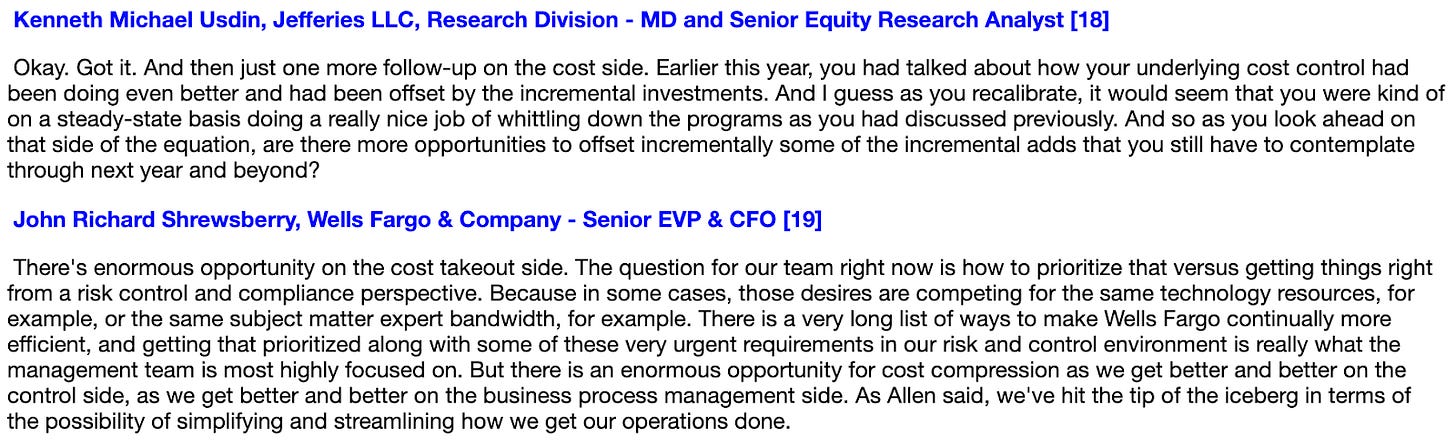

Wells Fargo’s stock has significantly underperformed the stock market and banking peers since the fake accounts scandal. The biggest reason for the underperformance is because the company’s cost structure has become bloated. Here’s John Shrewsberry, Wells Fargo’s CFO, answering a question about operating costs on the Q2 2019 earnings call:

Wells is investing billions of dollars annually in operating expenses to try to bring its compliance and controls to a point where it can successfully manage a bank. As Shrewsberry said, these costs are also taking away the company’s ability to make investments to increase efficiency, which are investments that other banks are making.

Let’s look at Wells’s cost structure in relation to JP Morgan and Bank of America, two of its large banking peers. I’m going to break the analysis up by business unit - retail banking, wealth and investment management, and wholesale banking - because different business mixes make a firm-wide comparison meaningless.

Retail Banking

First, let’s look at the retail bank. This is Wells Fargo’s biggest division by both assets and profits. The following charts show Wells Fargo’s efficiency ratio, which is defined as non-interest expense as a percentage of net revenues, so the lower the efficiency ratio, the higher the profit margin. Here are Wells Fargo and JP Morgan’s numbers from 2014, before the account scandal and at Wells Fargo’s height of profitability:

I’m leaving Bank of America out of this analysis for now because in 2014 it was having numerous problems and costs were elevated. As you can see, Wells Fargo had better margins than JP Morgan in 2014.

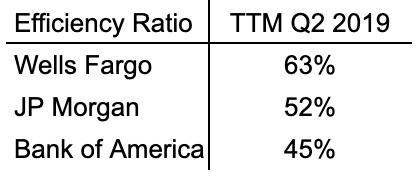

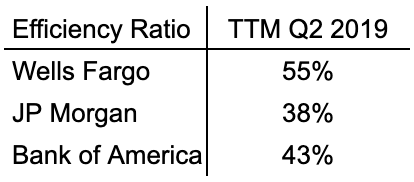

Now, let’s fast forward to the last twelve months (Q3 2018 - Q2 2019). Here are the efficiency ratios for Wells, JP Morgan, and Bank of America:

What a difference five years has made! While JP Morgan became much more efficient, with margins expanding by ~600 bps, Wells Fargo was going in reverse, with margins contracting by ~800 bps.

Zooming out, a central thesis for all of the big banks over the long-term is that technology will drive operating costs down as customers do more banking online or through an app. This migration has already started and helped profit margins tremendously, as you can see by JP Morgan’s results.

Wells Fargo’s costs, on the other hand, have skyrocketed in a period where its peers’ margins have expanded. It is unclear exactly how profitable Wells Fargo could be if it can get to a point where its investments in controls and compliance are normalized and they’re able to push efficiency, as Shrewsberry said they would, but the answer is clearly that the efficiency ratio should be coming down.

Wholesale Banking

Wholesale banking is a little bit harder to analyze, because Wells Fargo’s business is definitionally different than JP Morgan’s, as it is roughly three times the size and has a much higher efficiency ratio. However, I’ll still present the numbers:

For Wells Fargo, I’m actually using the average from 2012-2014, as results in any given year were lumpy. These numbers mean little in isolation, so let’s look at the trailing twelve month numbers:

We can see the same pattern that emerged at the retail bank - JP Morgan’s efficiency ratio improved while Wells Fargo’s got worse. The extent of the poor performance isn’t as bad as at the retail bank, likely because the retail bank caused many of the compliance problems in the first place. However, it’s still likely that Wells has some extra cost in this division.

Wealth and Investment Management

When presenting Wealth and Investment Management, banks quote a simple operating margin, so I’ll use that here. Margins at Wells Fargo were 24% in 2014. Here are profit margins over the last twelve months for the big three:

Again, you can see that Wells Fargo’s margins have worsened and are significantly lower than those at JP Morgan and Bank of America. While Wells Fargo doesn’t have the brand that JP Morgan or Bank of America (through Merrill Lynch) has in wealth management, it still looks to me like they have too much cost, as seen by their margins coming down over the past few years.

Valuation

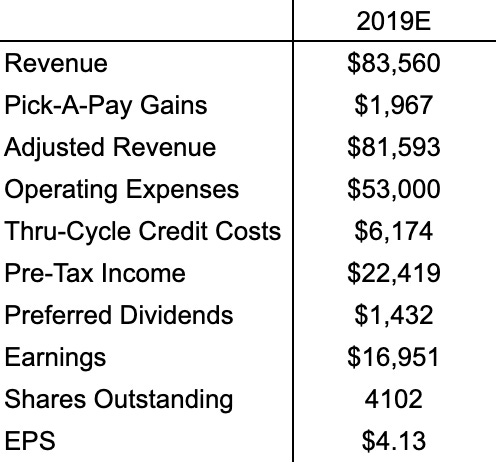

Before we start to talk about the potential for costs to come out of the business, I am going to walk through a quick earnings model for 2019. My goal is not to find 2019’s earnings. It is to find the rough earnings power of the bank, so I’ll make a few adjustments. Here are the expected numbers for 2019 with explanatory notes presented after the chart:

Notes and explanations:

Pick-A-Pay Gains - these are one-time gains from selling old mortgages bought during the financial crisis. Since they are non-recurring, I deduct the revenue to find “Adjusted Revenue.”

Adjusted Revenue - I am using net interest income plus noninterest income for this number. In their financials, they deduct provisions for credit costs in their revenue number. I will deduct this later.

Operating Expenses - all expenses except for interest expense and provisions for credit losses.

Thru-Cycle Credit Costs - the current strong economic means that current loan write-offs and loan losses are very low - Wells Fargo has provisioned ~27 bps of annualized losses so far in 2019, whereas Wells estimates that in an average year they will lose ~65 bps on their loans. I use this 65 bp number for average credit costs since I am trying to find average earnings power for the bank. Loans outstanding as of Q2 2019 are $950bb, which gives an estimate of $6,174bb in annual credit costs.

Shares Outstanding - to make the math a bit simpler, I’m treating dividends as repurchases. Additionally, I’m assuming that Wells uses half of its repurchase authorization of $23bb that will run through Q2 2020 in 2019 to arrive at my shares outstanding number.

With all of these adjustments to Wells Fargo’s earnings power, we can see that the bank should earn ~$4.13 in a normal year. Importantly, we have adjusted revenue downward to reflect one-time gains and we have increased average credit costs significantly to take a strong economy into account.

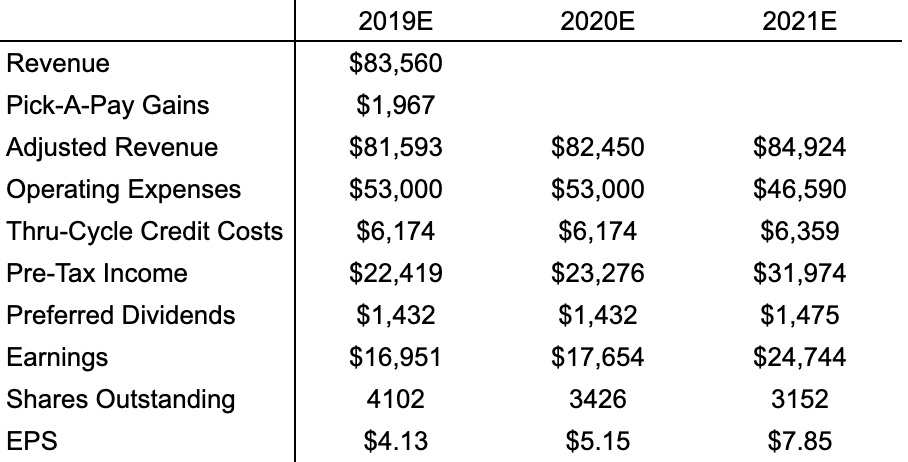

In order to complete our model, we have to extend the analysis out to 2020 because Wells Fargo has a significant amount of excess capital. It is in the process of distributing this capital to shareholders, but it will take perhaps another year or two to distribute all of it. We need to make sure we model this distribution. Here’s the same analysis but assuming that all of the excess capital ($18.1bb as of Q2 2019) is distributed by the end of 2020. I’ve also used consensus revenue estimates for 2020 along with the same $53bb in operating expenses:

Earnings scale higher as Wells is expected to earn more revenue next year on the same cost base. I’ve also assumed flat assets and loans due to the cap on growth in place from the Federal Reserve. Last, you can see that the shares outstanding are down significantly due to all earnings plus the remainder of the excess capital being returned to shareholders. To give you a sense of the exact numbers, I’m estimating that Wells actually earns $30bb over the next 6 quarters ending at year end 2020 and also pays out all of its $18.1bb in excess capital. Again, I have just added the dividends as repurchases, so the real number of shares outstanding will be higher, but you get the same effect if you reinvest the dividends.

So now we can start to get a sense of what Wells Fargo might be worth. I’ll try to find go forward IRRs given its current price of $45 and three different scenarios:

Asset cap stays in place, no costs come out of the business

Asset cap lifted, some cost comes out of the business

Asset cap lifted, Wells returns to near best in class margins

Scenario 1 - Asset Cap Stays, No Cost Out

For this scenario, we can just assume that the 2020 numbers we quoted above will become the new run-rate earnings. At the end of 2020, we will have earnings power of $17.7bb and 3.4bb shares outstanding for normalized earnings per share of $5.15. Since the balance sheet isn’t growing in this scenario, Wells doesn’t need any capital to fund growth, so all earnings are distributed to shareholders. That means that at a stock price of $51.50 at the end of 2020, you’d earn a 10% return over time. If you discount that back to today at 10%, you get a price of $44.70, very close to today’s price. We’ll round a bit and say that in this scenario you can expect to earn roughly 10% returns going forward.

Scenario 3 - No Asset Cap, Best In Class Margins

Please note that I’m skipping ahead to scenario 3. We’ll use the best case scenario in order to back into our second scenario.

In order to find an estimate for how much cost Wells Fargo could take out of the business if it goes back to being run very well, we’ll look at the previous section where we compared its margins against JP Morgan and Bank of America, we’ll assume a margin, and we’ll multiply it against the revenue of that unit to find its earnings power.

First off, the retail bank. The retail bank had TTM revenue of $44.6bb and an efficiency ratio of 63%, so roughly $28bb of cost. However, $2.6bb of this revenue was from one-time pick-a-pay mortgage gains that would have come in with very little to no associated cost. If we deduct that revenue out, we have real revenue of ~$42bb and costs of $28bb. If Wells goes back to operating efficiently, it’s reasonable to assume they could get to an efficiency ratio around 50% (in between 45% at BAC and 52% at JPM), which would translate to $7bb in less cost.

On the wholesale side, Wells’s business looks different than Bank of America’s and JP Morgan’s, so we can’t do a direct comparison, but we could assume that, just like JP Morgan’s margins are a bit better than they were in 2014 that Wells Fargo’s could be as well. Wells Fargo’s efficiency ratio was 52% in 2014 and is now at 55%. If we assume it could get to 51%, then that would be $1.2bb of cost out of the business.

Last, on wealth and investment management, I’ll also assume that Wells gets back to 2014 margins of 24%, up from a current 21%. That would reduce costs by $400mm annually.

If we add that all up, we have a case where $8.6bb of cost could potentially come out of the business. Is this aggressive? Clearly. But you could see from the section above just how out of whack Wells Fargo’s cost structure is. There’s clearly lots and lots of room to cut expenses.

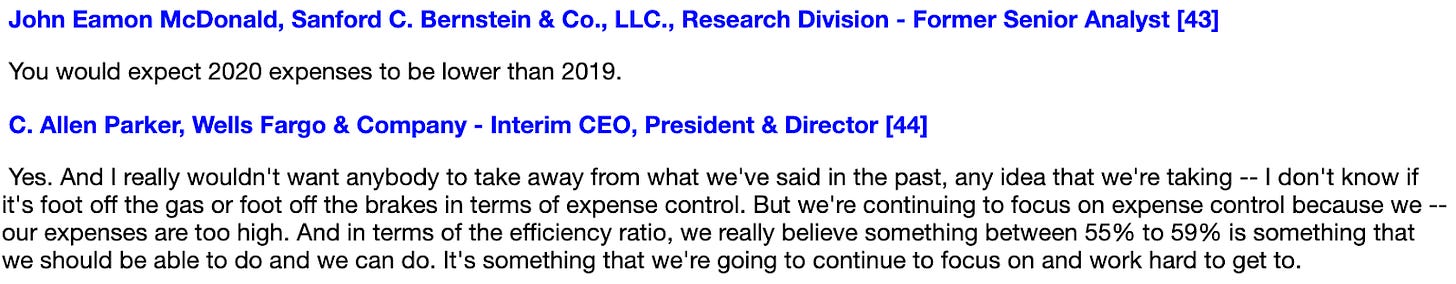

One more data point would be the combined efficiency ratio for the whole bank. If Wells removed $8.6bb of cost out of its business its combined efficiency ratio would be 54%. A few months ago, Allen Parker, Wells Fargo’s temporary CEO, had this to say about its efficiency ratio over time:

So clearly taking $8.6bb in cost out of the business is in the realm of possibility. If we use $8bb instead of $8.6bb, we’d get the combined efficiency ratio to about 55%. That’s a bit more conservative and also lines up with Parker’s comments, so we’ll use that for the model.

The last piece now involves asset growth, since we’re assuming the asset cap lifts. For the big banks, I assume 3% long-term asset growth. Big banks should be able to keep growing deposits and loans over time as the economy grows and customers continue to prize the ease of use that big banks provide.

Using our estimate of $8bb in cost out of the business and 3% growth, we can estimate Wells Fargo’s terminal earnings power. I’ll present this earnings power as accruing in 2021 even though it would likely take a few years for Wells Fargo to get to this level of efficiency. I do this, honestly, because it makes the modelling easier and all I’m really concerned about is getting the numbers roughly correct. Here’s how it looks:

Everything has scaled by 3% except for operating expenses, which have dropped by $8bb below the expected level. I have also reduced shares outstanding by 8% due to continued buybacks and dividends.

What types of returns would we expect from the current stock price of $45? If you just discount the cash flows from the current price you get an IRR of ~13.5%. Realistically in this scenario you might expect Wells to trade at 12-13x earnings at the end of 2020, or roughly $95-100. That would be a little more than a double in 2.5 years. Again, I want to emphasize that not all the cost would come out immediately. Perhaps it would take 5 years to get all the cost out. In that case you’d be looking at roughly high teens IRRs or a bit higher until you get to peak efficiency.

Scenario 2 - No Asset Cap, Some Cost Out

We’ll just build off the work from the previous section here. I’ll still assume 3% asset growth, but this time I assume $4bb of cost comes out of the business. That’s about half of the best case scenario and would translate to an efficiency ratio of ~59%, also the top end of the CEO’s target.

Here’s the same model from the above section with the new $4bb number for costs:

In this case, a simple DCF would get you to ~12% IRRs from the current price of $45. If we assume that the stock re-rates to 12x earnings (it should be a lower multiple than before given the lower return on equity, which itself translates to less FCF given some expected level of growth), then it would be worth ~$82 at the end of 2021, good for an 80% return. Again, if it takes five years to get the cost out, you’re looking at mid - high teens IRRs.

Valuation Summary

Going through those scenarios, we can see that in a case where Wells Fargo continues to have significant operating challenges, market by a continued asset cap and no costs coming out of the business, buying shares around $45 should still get you ~10% annualized returns going forward. If Wells takes some cost out of their business and the asset cap is lifted, then investors might see mid-teens types of IRRs over 5-6 years as the bank becomes more efficient. If Wells goes back to being close to best-in-class, IRRs over that same time frame could be around 20%.

This looks very attractive to me, as my base case is for some improvement and maybe $3-5bb of costs to come out of the business over the medium term. If I’m wrong, and no cost comes out, then it’s still a ~10% return, which meets my personal opportunity cost of capital.

Risks

While the IRRs I quoted look quite attractive given a probable range of scenarios, we need to address some risks. First, we’ll look at a couple of large risks to banking itself, then we’ll look specifically at Wells.

Banking Risks

We’re already addressed the risk of losing deposits, so I’ll move on to what I consider the other two biggest risks to any bank - poor underwriting and net interest margin compression.

Poor underwriting has traditionally been the main cause of any failed bank. When you hold assets against liabilities with leverage, if the assets lose value you can quickly find yourself insolvent. Charlie Munger, in his typically pithy style, commented “The liabilities are always 100% good. It’s the assets you have to worry about.”

Because of this risk, I would only consider investing in a bank if I’ve watched it operate through an economic cycle. Wells Fargo generally avoided lots of the foolish underwriting of its peers during the period leading up to the great recession in 2008-2009 and probably didn’t need the federal bailout money that it was forced to take. Wells has always been a rather conservative bank, and there’s nothing to suggest that that has changed. In fact, the regulatory regime after the great recession has probably forced banks too far the other way on the risk scale - there’s lots of loans that big banks could underwrite but can’t because of regulation.

The second large risk would be net interest margin (known as NIM) compression. Banks’ spread between what they pay depositors and other creditors and what they make on loans typically widens with higher interest rates and a steeper yield curve. If rates go lower and the yield curve becomes flatter, as we’ve seen in Europe, that could squeeze Wells Fargo’s ability to earn a good spread on its assets and liabilities.

Unfortunately, there’s no great way to estimate a bank’s earnings power in drastically different interest rate scenarios. The best I can come up with is that returns on tangible assets tend to be higher with higher interest rates and lower with lower interest rates. But you have all sorts of other variables like refinancing volumes and fees which make the analysis difficult. Furthermore, if the 10-year treasury bond yield dropped significantly from its current level of ~1.5%, then any earnings that Wells Fargo does generate should be worth much more than they are now because of lower discount rates for equity investors. The same goes, in the opposite direction, if the 10-year yield increases significantly - higher earnings but a higher discount rate. Taking all of these things into account, I would guess that Wells Fargo is worth less with much lower interest rates and worth more with higher rates, so you do have macro risk in this situation. How much, exactly, is anyone’s guess.

Wells Fargo Specific Risks

The current opportunity in Wells Fargo exists precisely because management has been so bad at running the bank. All of the scandals have led to less deposit growth and high costs. A big risk in this situation is that management continues to run the bank ineptly and things don’t really ever get better.

While this is a significant risk, what makes me okay with it is that the current price of Wells Fargo’s stock more than pays you for taking it. As we found in the first scenario, if the asset cap is never lifted and Wells Fargo can’t take any cost out of its structure, then investors still have a ~10% free cash flow yield. For management ineptitude to really harm shareholders, things actually need to get much worse and stay worse for many, many years.

I also actually think that it shouldn’t be impossible to get things changed. I wrote a book review on my blog about Kochland, which details the history of Koch Industries. Koch infamously incentivized ROI above everything else, which led to huge amounts of safety and environmental violations and catastrophes in the 1980’s and 1990’s. Finally, Charles Koch changed the incentive scheme around to mandate 10,000% compliance, or 100% compliance 100% of the time. Compliance and safety improved dramatically after the change.

A friend of mine on twitter, @soonercapital (worth a follow if you don’t already!), messaged me and said, “Can’t help but think of the parallel of WFC and [Koch]. A good historical analog for correcting incentive based problems.” I think he’s exactly right. When you have problems due to incorrect incentives, if you change the incentives then you can change the outcomes pretty quickly.

I’m optimistic that Wells Fargo’s management can fix the situation for a few years. Even if they can’t, investors should still do pretty well from these levels.

Conclusion

Although Wells Fargo has some risk, I believe that the current price more than pays investors for taking it. We’ve seen that banking is an attractive industry if you have a large, low-cost deposit base, because those deposits prove to be quite sticky. Big banks are also advantaged due to their ability to serve customers with excellent technology solutions for their banking needs, and making banking easy is mostly what customers care about.

We’ve also seen that Wells Fargo’s historical problems have caused its cost structure to balloon while peers have become more efficient over that same time frame. If Wells Fargo can become a bit more efficient over time, returns to investors should be quite strong. If Wells Fargo can become the great bank it once was, returns will be even better. The improvements might take some time to come to fruition, but long-term investors should be rewarded.

Disclosure: Pursuant to the provisions of Rule 206(4)-1 of the Investment Advisors Act of 1940, we advise all readers to recognize that they should not assume that recommendations made in the future will be profitable or will equal the performance of past recommendations. This publication is not a solicitation to buy or offer to sell any of the securities listed or reviewed herein. This contents of this publication are not recommendations to buy or sell any of the securities listed or reviewed herein. Investing involves risk, including risk of loss. The contents of this publication have been compiled from original and published sources believed to be reliable, but are not guaranteed as to accuracy or completeness. Kyler Hasson is an investment advisor and portfolio manager at Delta Investment Management, a registered investment advisor. The views expressed in this publication are those of Kyler Hasson and not of Delta Investment Management. Kyler Hasson and/or clients of Delta Investment Management and individuals associated with Delta Investment Management may have positions in and may from time to time make purchases or sales of securities mentioned herein.

[jetpack_subscription_form show_only_email_and_button="true" custom_background_button_color="undefined" custom_text_button_color="undefined" submit_button_text="Subscribe" submit_button_classes="undefined" show_subscribers_total="false" ]